a tv critic is normal about procedurals

kelly connolly on the bones of television and Bones, of television

Kelly Connolly is a senior editor at TV Guide and a former editor at Entertainment Weekly whose interests include repressed straight couples written by Vince Gilligan and repressed dads played by Victor Garber. Today she is feeling normal about television procedurals, which, at their best, “capture the unknowing quality of the world,” and, at their worst, are 500 billion episodes of CSI: Miami. Your mileage may vary, but Kelly argues that everyone needs at least one show about people who really love their jobs…to make you existential about your own.

This interview has been edited for clarity, coherence, and vibes.

NICOLE: What are you feeling normal about, and how did you first encounter it?

KELLY: I'm feeling normal about the TV procedural, as a concept. There are obviously many procedurals that I have no feelings about, and so many others that are bad, but I'm very serious about defending the procedural as a format.

I probably first encountered it through TV Land reruns of early procedurals like Dragnet, but only because that was what was airing on summer afternoons, not because it was something I was remotely passionate about. I didn't find procedurals that I was passionate about until later, and I didn't realize that I was passionate about the procedural until even later than that.

JADIE: When you say the “procedural as a format,” what do you mean?

KELLY: A procedural is typically a show about characters who work in law enforcement, or who work in the medical field or any kind of detective field, solving or attempting to solve problems as part of their work. Obviously, there's a lot that I think is really damaging in terms of American pop culture when you go back to the very early origins of the TV procedural — I think it’s rooted in propagandizing cops as heroes, or as trustworthy characters who can solve problems for you.

But at its core, a procedural gives you the opportunity to feel like you're going to work with the characters, and if you like the characters, you want to keep going to work with them. The format tends to be set up as an opposition to a more serialized form of drama: there's a case of some type that is investigated over the course of an episode, and ideally you find an answer by the end.

NICOLE: How does a good procedural keep you coming back for more, especially if it’s just more of the same?

KELLY: With some shows, it’s because you enjoy hanging out with the characters — I think every procedural to a certain extent depends on that. The structure provides a really good basis for relationships to take center stage. Obviously, there's the will-they-won't-they component in so many procedurals, but even beyond that, you can just easily track changes in relationships.

Some shows also have a comfort element that comes from the audience wanting to watch a problem be solved. And then others — the X-Files realm of procedurals, which I would usually consider to be more sophisticated — are subverting that expectation for easy answers, but they’re still providing a vehicle for characters to ask questions.

We tend to think about the procedural only as being a very mediocre show on CBS or something, but it’s just a style of telling a story. It can be as good or bad as any other show’s style, and it can keep you coming back for any number of reasons. And eventually with every procedural, you can feel the network coming through it, whether or not it was written for a specific audience. You can eventually see the show tailoring itself to that audience, which happens with a lot of network shows.

If you look at something like Hannibal, that was a show that wanted to be transgressive, and I think being a network procedural made it more transgressive by default, because it starts from this shared language that we all have. Regardless of how many procedurals someone has seen, we all understand what the basic idea is, because it's so built into American pop culture. We all have an expectation for the format, and the show can either complicate that or find some new potential in it. If you care about television as a medium, you have to be able to understand this really basic format as something that is not inherently going to produce the same kind of show every time.

NICOLE: What keeps you coming back to the procedurals you watch? Is it the problem solving, or the relationships?

KELLY: I think it's been different things for different shows. If I’m being honest — and what is this conversation if not that? — the first procedural that I got really, frighteningly into was Bones, which I started watching when I was studying abroad. I was having a bad, lonely experience, and I was very adrift in a way that drew me to the comfort of watching characters solve problems.

That's by far the most classic of any of the procedurals that I've been into. I’m usually much more drawn to a show that’s at odds, inherently, with the procedural expectation for answers. Something like The X-Files or Buffy or Evil — those are all shows that are using the procedural in order to ask questions about whether closure is possible.

NICOLE: When you finish a really good episode of one of these shows, what’s the feeling you associate with that?

KELLY: I think if you're talking about a procedural that does offer a sort of stereotypical resolution at the end, the feeling I associate with that is that I need to find my purpose in life. [Laughs] It kind of makes me want — not to do that kind of job necessarily, especially depending on what the job is, but it makes me want to feel like I'm doing something that makes a difference. And if you're not, then maybe you can at least watch TV characters who are, or who you imagine are.

When I'm watching something like The X-Files or Buffy or Evil, something that doesn’t offer that easy resolution, then I think more about the potential of art to capture the unknowing quality of the world, the inability to find closure. With The X-Files, I enjoyed the way the show opened up room for doubt, which is the opposite of what Bones was doing. I think that came from having been raised in a family that expected me to have a certain amount of religious certainty, and then hitting my 20s and realizing, Hmm, maybe not. I really liked watching a show that gave the characters an engine to look for answers but rarely find them; to sit in that doubt was something that I found very comforting in its own way.

Something like Buffy is a really good example of a show that uses uncertainty to reflect the experience of growing up, and to specifically suggest that when you’re young, you think that things will be easier to figure out when you’re older, and they’re not — and that conversely that when you're young, adults think that you have it easy, and you do not.

I'm drawn to any story about finding some level of peace with uncertainty, because that's something that I'm still trying to reach in my own life. I'm interested in the idea that maybe you can only tack meaning onto certain experiences through something like art, and so when a show manages to give me that, I’m simultaneously comforted by it, by art as a concept, and by writing and storytelling.

JADIE: And maybe there’s something in the fact that the uncertainty can repeat itself through the same formula — like, not every uncertainty is the most uncertain, or the final frontier of doubt.

KELLY: Exactly. I think the idea of finding no answers, or not the answers you wanted, but continuing to search and ask questions anyway is really beautiful. I think that’s one of the best things about The X-Files, and I think Evil also captures that really brilliantly.

When a show can give you that feeling that maybe the highest thing that you can hope for is not to actually find the answer, but to continue to search for it and to find people who will search with you...I think that's something that a procedural can do well, precisely because of that repetition, and precisely because it is about people going to work, and the work is just asking questions. There’s something almost academic about that.

JADIE: I’m interested in how much the labor of procedurals matters. For instance, a show like The Pitt is very detailed about the work characters do, and people watch it for that reason. But you also have people watching because they want the doctors to kiss.

KELLY: Yes. And I’ve obviously been guilty of watching a show for the central relationship —

JADIE: Who hasn’t?

KELLY: Who hasn’t! And there is so much to be gained by it. It's almost harder, in some ways, for a show that doesn't have, or isn’t relying on, a serialized relationship arc to still make you really care about these characters. You care about them because they spend time with each other, not because you’re watching them and thinking, I want them to be able to overcome this obstacle.

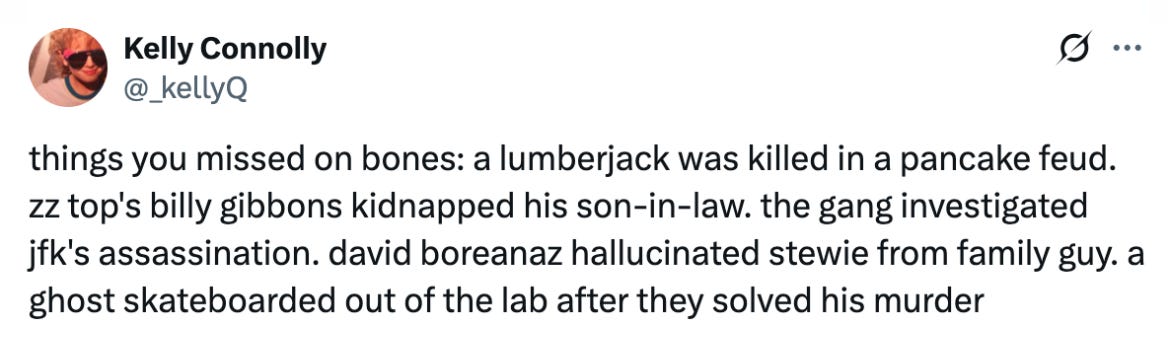

In the case of Bones, that was one that I was watching for that very traditional reason, where I was just enjoying the comfort of watching these characters at the top of their fields do their jobs. But at the same time, that was the first show that I was watching for the central relationship, where the will-they-won’t-they was really driving me. Especially as the show goes on — because it lasted for 12 full seasons — you reach a point where maybe the only thing that's working consistently is the dynamic between the characters.

I think that the joy of a good procedural should come in part from the work. It should come from watching characters investigate, regardless of whether that investigation leads to answers or not. The procedural’s focus on work also makes it a really good vehicle for repression, which is one of my favorite things for a story to explore. I think that the plot sort of necessitates repression, because the characters have to be able to set aside their emotions in order to do their jobs, or at least channel their emotions through their jobs. I think that speaks to the temporality of the procedural, the day-to-day quality, because it allows these personal revelations to be the long-term point of the show. They're doling out these moments for the characters in these tantalizingly small doses, so you have to come back to see it all come together. And the work is what they put in between those moments.

But at the same time, the work can also become the meaning and the point. Like, if you look at The X-Files, Mulder searching for his sister is the inciting incident of the story, but then the way the show is constantly sending him on all these little side quests to investigate other cases — that sort of becomes the point. It's like the show is forcing him to slow down and look at the world around him, and the format is a way to not necessarily have to confront things head on.

JADIE: You said repression is one of your favorite elements of a story — what’s up with that?

KELLY: I think people have subtext. I think that people don't always say what they mean, so it tends to ring false for me when people on television say what they mean. I'm more interested in shows that leave a gap between what's being said and what's being felt, something that allows for interpretation, something that draws the viewer in. I want there to be that sort of blank space where I can bring myself into it, and I find the characters being a little bit repressed tends to allow room for that.

NICOLE: When it comes to a more traditional network procedural like CSI or Law and Order, someone like my nana is as likely to be watching as a TV critic. Do you think you guys are engaging with procedurals in different ways?

KELLY: I'm sure we are. It’s funny, because I don't feel like I'm ever talking to people who are only watching procedurals; I feel like I'm talking to people I have to fight to get to take procedurals seriously.

The critical conversation around procedurals is really interesting. It’s other people that I feel more out of the loop with. You could have the same conversation about reality TV, where someone who is really engaged in the messaging of reality TV is simultaneously on a different wavelength from people who are watching it uncritically, but also on a different wavelength from people who think that they're too serious for it.

JADIE: If someone wanted to become normal about the TV procedural, where would they start?

KELLY: Evil would be a good one to start with, although your mileage may vary. But the seasons are short and the quality is really consistent from episode to episode. Something like The X-Files or other ’90s shows that have 200 episodes...those go up and down in quality from week to week. So if you start with a procedural that has more of a streaming rhythm, you can build your stamina.

NICOLE: That’s so funny, because I feel like if I’d watched a lot of procedurals, I would be like, You need to earn your stripes by watching all 500 billion episodes of CSI: Miami.

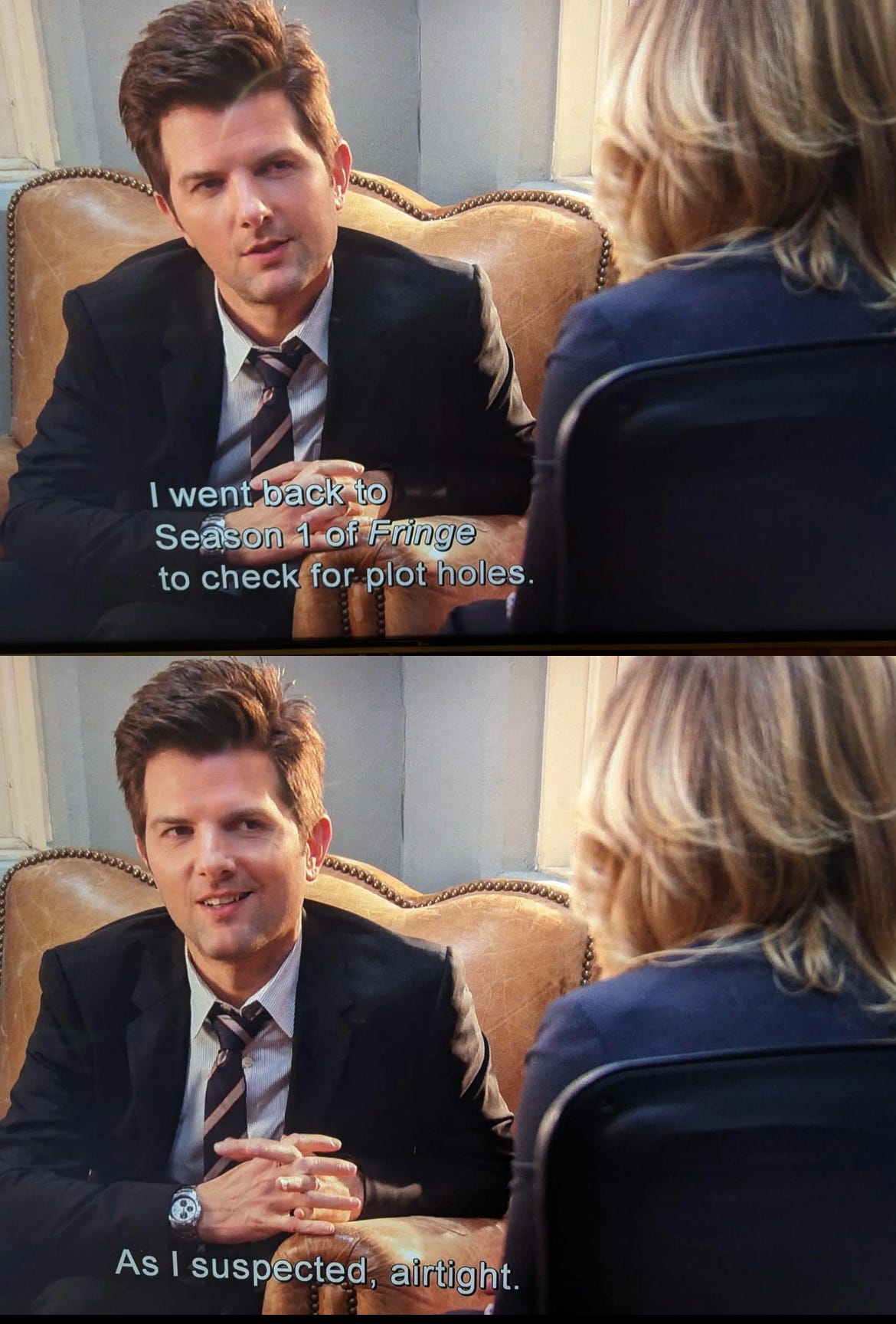

KELLY: My thinking is more like, How do I make people respect the format? I’ve been seeing newer X-Files viewers on the internet who seem like they’re watching the show while hating the format of the procedural. There’s a lot of performative self-loathing where they’re like, It's not good, but I'm watching it. And it's like...this is actually not only one of the best procedurals ever made, but one of the best TV shows of the last century. The only explanation that I could find for that argument was that these people are just inherently not trusting the procedural as a format. So I think it might be good to work your way up to something like that.

But then on the flip side, maybe you do have to have at least one middling, Bones-style procedural that you are, at the very least, familiar with and have some affection for. You don't have to be obsessed with it, but you have to have some affection for it, because if you don't have that experience — if you don't have a Bones in your life — then when you watch something like The X-Files, you don’t see it. Maybe you should, but clearly there are people online who don't have their heads on straight. [Laughs]

NICOLE: Are you better or worse for knowing about procedurals, and is the world better or worse for procedurals existing?

KELLY: If the question of whether the world is better or worse for procedurals existing, that’s complicated because of the damage the format may have done to the American psyche with regards to cops. Although I can't entirely demonize it, because a detective procedural can just as easily be flipped on its head and become a noir, anti-cop story.

But I’m better for the procedurals that I've enjoyed. There are obviously all the reasons why any show can make a person's life richer because of friendships, or because of things that you take from it into your own life — but my work is also benefiting from the fact that I appreciate the history of this medium that I'm writing about.

JADIE: Well, I feel like the procedural’s good name has been saved today. And when this goes out to our five subscribers —

NICOLE: My nana, your nana...

KELLY: The Emmys will be like, we should give one to Evil.

JADIE: They’ll be shaking in their boots.

This one goes out to the Emmy voters. It's not too late to do the right thing and watch Evil.

Loved it! I’m all in on procedurals although for some reason I’m normal about every British and Nordic procedural out there. Something for me to ponder now.